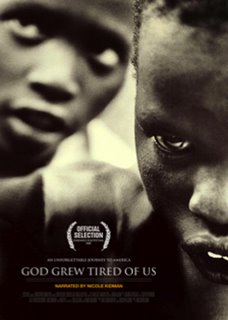

God Grew Tired of Us

2003’s Lost Boys of Sudan startled the world and bowled over critics. Now, in 2007, comes an unintentional companion piece in God Grew Tired of Us. Covering some of the same ground but with a longer scope (filming took place over four years), God Grew Tired of Us is no less noteworthy and powerful than its predecessor and comes at a time when we can all deal with being reminded of the horrors of Sudan and Darfur.

Brad Pitt produced and Nicole Kidman narrates this harrowing, powerful and even hilarious film about culture shock, retaining one’s national identity, and life’s utter refusal to be eradicated. God Grew Tired of Us is one of those rare and unique films that can extract wailing tears and wailing laughter in the same moment.

In 1983, roughly 25,000 boys from Sudan, most younger than 10 years-of-age, fled the encroaching Muslim army bent on exterminating them. Two million people were already dead. The children trekked on foot for more than 1,000 miles, during which many of them died, eventually arriving at a U.N. refuge camp in Kakuma, Kenya as skeletal ghosts of their former selves. “Life,” one of the boys says, “is waiting for your grave.”

Trapped for over a decade in a limbo land, the nearly 100,000 boys grew up in a makeshift family, banding together into a close-knit society in which they all took care of each other. It is remarkable that despite having nothing except each other and their nightmares, the boys’ human spirit is indomitable and unbreakable.

Numerous (though not nearly enough) countries, including America, agreed to resettle some of the refugees. Enter director Christopher Quinn. His camera, which always seems to be at the right place at the right time, selects three intelligent, eloquent and charming young Sudanese men at the camp—John Bul Dau, Panther Bior and Daniel Abul Pach—as they prepare for life in the United States.

It is amusing to listen to the boys as they anticipate life in the United States. The filmmakers allow us to smile at the boys’ cultural insecurities and misconceptions without ever once condescending to them. One boy fears that electricity will be very difficult to learn while another wonders what rivers Americans go to in order to gather water for their baths. Their false impressions range from the humorous: “In America we hear you can have only one wife” to sad indictments of our own country’s failures: “In America, you never go to bed hungry.”

Leaving the camp is bittersweet. Despite the squalor and lack of opportunity, those lucky enough to be going overseas nevertheless leave behind the only family many of them have ever known. For the first time they encounter a world more like a science fiction movie than reality. They are entranced by the buttons on telephones, flummoxed by escalators, hypnotized by televisions, spellbound by newspapers, and flabbergasted at the jet airliner that wings them to their new home. One particularly perceptive young man observes that the plane food is worse than the food he’d been eating at the refuge camp.

One of the funniest scenes in the film comes when the boys are shown around the apartment they will all share. The most basic things must be spelled out in child-like detail and their reactions to light switches, refrigerators and toilets are endearing. Supermarkets are beyond comprehension. “In our country, we call this Coca-Cola," says another young man, pointing to a bottle of Pepsi. Their American hosts are little better. They stare at the young men with bewilderment and confusion. They have no idea where to look for Sudan on a map. And their grossly inflated stereotypes are as laughable and erroneous.

But these admittedly amusing fish-out-of-water moments are nothing compared to what the boys face as they try to adapt to a wildly foreign culture. As their stay extends into months, their loneliness and even survivor’s remorse is palpable. Their indigenous spiritual values clash with the overt commercialism of the Western world (“Where is Santa Claus in the Bible?”). They battle cultural assimilation and strive, sometimes unsuccessfully, to hold onto their native culture.

Following the initial phase of shooting, director Quinn returned every few months for the next several years to check on the men’s progress. His gorgeous-looking, briskly-paced and crisply-edited film reveals the transformation of young, timid boys into full-fledged men. Not simply responsible adults—though that is implicit in a reality in which the Lost Boys wake well before dawn, usually working three jobs a day so they can send all their money back to Africa in the hopes it reaches their surviving loved ones—but proactive ones, organizing, challenging and politicizing for the cause of their homeland. They become self-described ambassadors for the Sudan, committed to helping their friends and family back in the camps.

“Are we not human beings like other human beings (in Europe)? Can we not be helped,” asks John Dau, who is the natural leader of the group. “When somebody is in pain, the best way to help is to become involved in their problem.”

His are not empty words. At a brief Q&A after a recent New York City screening, Dau was on hand along with Christopher Quinn to answer the questions of several hundred mostly educators. He bemoaned the continuing sad state of affairs in his native land and the wedge of religion that split his country in two. He urged those gathered to become more active, to engage the media in keeping Sudan and Darfur front and center in the national consciousness, and to volunteer or, if possible, contribute to the cause.

Now married (to a Lost Girl) and proud father of newborn baby, Dau, who in his former life was a cow herder, has now completed college, spoken on behalf of his beloved country to heads of state, and raised over $154,000 for a medical clinic in his home village which has never had such facilities.

“Where there is a unique need, you have to invent something,” Dau said. “You have it within yourself to do that too. If I could do it, you can do it.”

Quinn, who admits to making the film because the world wasn’t paying enough attention to the problem, said, “I felt there had to be a way to express what was taking place in Africa, not only in the Sudan but also in Rwanda and the Congo.”

Both the main character in and the largest proponent of the film, John Dau sees God Grew Tired of Us and other media-centric calls to arms as the most potent way to rouse American audiences to action.

“Christopher told me from the beginning that this film is how we are going to spread the word (about what’s going on in the Sudan). Such is the power of media.”

4 Comments:

Very well written. And it sounds very interesting and moving.

Thanks for your great post.

John Dau has joined Direct Change as the Director of our Sudan Project. Direct Change provides online tools to allow supporters to build support for African projects. The Sudan Project is foucsed on raising support for projects to rebuild southern Sudan.

Join John at: http://www.directchange.org/sudan

Excellent review, Brandon. This is the kind of movie I wait for. Following such current events through the press is concerning enough, but a film like this will really connect. I really want to see it.

This sounds like an amazing film. Regrettably, I have yet to see Lost Boys of Sudan, though I have every intention to.

Post a Comment

<< Home