Into Great Silence

“The Lord said, 'Go out and stand on the mountain in the presence of the Lord, for the Lord is about to pass by.' Then a great and powerful wind tore the mountains apart and shattered the rocks before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind. After the wind there was an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake. After the earthquake came a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire. And after the fire came a gentle whisper…” -- I Kings 19: 11-13

In 1984, German filmmaker Philip Groning approached the Carthusian monks, considered the Catholic Church’s strictest order, for permission to film their monastic lifestyle. They responded that they were not ready for him.

In 2000, almost two decades later, Groning got the phone call he’d been waiting for. He was finally welcome to come. And Into Great Silence (watch the trailer) was born.

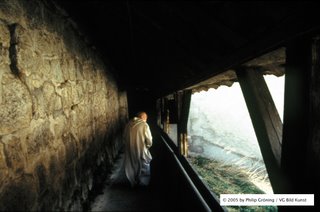

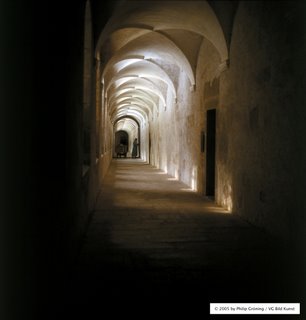

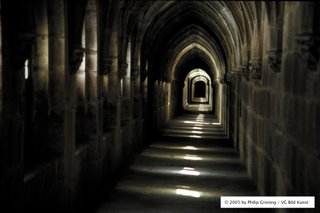

Groning lived as one of the monks for six months in the picturesque Grande Chartruese monastery, a medieval enclave built into the side of a hill beneath the shadow of the monolithic French Alps outside Grenoble. He carted his own gear, shot his own footage, recorded his own sound — all without the benefit of assistance or supplementary lighting. Sometimes his camera captures exquisite clarity; other times it registers barely enough light to decipher an image — and yet, regardless, each and every shot is magnificent.

This film isn't interested in merely recording the mundane activities of monastic life, but rather immersing the viewer so completely that the barrier between projection and reception vanishes completely. Never has a camera been more intimate or observed as closely. It becomes a thing metaphysical rather than mechanical, trading the natural for the supernatural.

It is a well-known fact that once someone goes blind, their other senses are hyper-sensitized. There is a monk in Into Great Silence who has gone blind and now threads his way through the monastery’s passageways with a tentatively probing cane. His untrimmed eyebrows are so long they hang over his useless eyes like a feathered shroud. He praises God for his malady, confident that it allows him to focus unhindered on his worship.

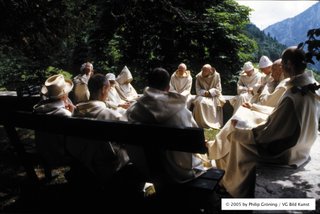

In a very real way, the audience is like that monk. The brothers of Grande Chartruese have taken a vow of silence, and aside from prayers, chants, and a once-a-week excursion outside during which they are allowed to converse with one another, there is no dialogue in the film. Nor is there any sort of musical score. For over two and a half hours, we simple exist as one of the monks, living as they live, our 21st-century polluted minds desperately trying to understand our suddenly hyper-perceptivity.

It is a mistake to say this is a silent film. If anything the absence of human speech reveals how much sound we miss. This is a soundtrack of sandals slapping marble, gurgling brooks, songbirds, the swish of fabric, the rustle of pages, the ringing of bells. So powerful is the silence that it seems to embody a sound all its own. One begins to imagine the noise light makes as it streams through windows, splashes across wood, reveals dust particles dancing in the air.

Director Gronig captured the introduction of several new initiates into the brotherhood, including a strikingly beautiful young African, the only man of color in a sea of mostly elderly white, bearded faces. He takes his vows and visits the barber, where his head is shaved in a scene eerily reminiscent of a half-dozen military boot camp films. This simple act is one of the few moments during which there is any sort of physical contact between the men.

As with their worship services, the hermit monks of Grande Chartruese live their lives in the thrall of liturgy — a sacred rhythm of prayers, mass, study, work, physical labor — a ritual essentially unchanged in the order’s thousand year existence. The film opens with the alpine campus hemmed in by deep drifts of bitter, blowing snow. Soon the snow will melt, verdant buds will crack the permafrost and spring will appear. And by the time the film ends, winter will have returned. The circle of life is seen in the seasons, the daily routine, the young men entering the monastery where old men now tread. It is a cycle of harmony — with God, with themselves, with nature, and with their own souls.

The monks spend most of their days in their tiny cells, lost in prayer and solitude. Theirs are lives of unadorned simplicity. Having embraced a life of destitution and poverty, their living spaces are austere and spartan, ascetic shells devoid of any earthly distraction. A straw bed, a tiny tin stove and a desk are all that adorns their cell. They spend their days largely alone, only coming together for mass in the chapel and at the Sunday noon meal. When not cloistered in prayer, they wash their own clothes and dishes, prepare meals, garden, cut wood, read or engaging in chores. Even their nights are not their own. The monks do not sleep through one full night in their lives, waking for several hours in the middle of the night for collective prayer.

Once a week, after the Sunday noon meal, the monks are allowed four hours rest time in which they take a walk into the forests surrounding the monastery. During this time, they are allowed to freely talk amongst themselves. More often then not, the conversation still turns to issues of spirituality, faith, philosophy and the daily practice. On one snow-bound outing these pillars of religious devotion devolve into schoolboys, using their flowing robes as makeshift sleds to careen down steep hillsides to the giggling delight of their brothers below.

Punctuating the film like chapter markers, Gronig captures his subjects in close-up, pausing for long moments to allow the monks to look directly and often uncomfortably into the glass eye of their beholder. It is amazing how much individuality and personality these men have, despite the fact that we hear so few of them ever utter a word.

Some of Into Great Silence’s most haunting moments occur when we are reminded of the unavoidable presence of modernity: a massive jetliner streaks silently through the sky, the abbot manages the monastery’s finances on an old laptop computer, a novice practices his chants with the aid of a small, electronic keyboard. These moments jolt our senses, crack our reverie and remind us that this is a film and not a time portal into a world long past.

Into Great Silence is hypnotic, lulling the viewer into a trance. It is not a censure to say that at times you feel sleep tugging at the edges of your consciousness; the film is so serene and tranquil that it is a testament to the craft and subject matter. This is more meditation than movie — a mesmerizing, poetic chronicle of spirituality.

You are aware, while watching, of just how much you have and just how much you lack; of the omnipresence of the divine in the most mundane of activities; of the pervasive majesty of the natural world utterly squelched by our urban lives; of the inspiration these men arouse. To watch this film is to be humbled. To watch this film is to be in awe. Into Great Silence is a transformative theatrical experience, a spiritual encounter, an exercise in contemplation and introspection, a profound meditation on what it means to give oneself totally and completely, reserving nothing, to God.

I have never before experienced a greater example of utterly transcendent filmmaking.

And then the lights came up, and I shuffled out onto the street and was greeted by the angry din of Manhattan. It was almost enough to make me weep.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home