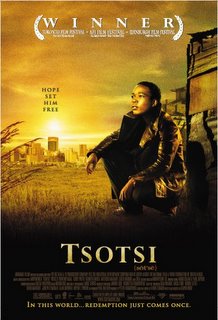

Tsotsi

I write film and TV reviews at DVDFanatic.com. Here are synopsis' and links to those reviews.

Tsotsi, the first Miramax release without the fabled Weinstein brothers at the helm, bodes well for the future of the production company that turned independent filmmaking into a Hollywood juggernaut. The Oscar winner for Best Foreign Film is well-deserving of the honor, a film that is simple without being simplistic, profoundly moving without ever once veering into sentimentality, an emotionally honest tale of redemption that does not ignore the fact that we live in a world of cause and consequence.

Adapted from acclaimed South African playwright Athol Fugard's only novel, Tsotsi was originally set in the 1950s. Writer/Director Gavin Hood has updated it to the post-apartheid present to reveal a tragic reality: for many black South Africans, little in life has changed. Tsotsi does more than just expose South Africa’s criminal underbelly, it starkly depicts the deep social rifts that threaten to destabilize the country as a whole.

Disenfranchised by whites and wealthy blacks alike, South Africa’s poor are besieged by crime, drowning in poverty, and blighted by AIDS. In highlighting the disparity, Tsotsi makes a powerful statement about what’s still wrong in post-apartheid South Africa. Like another Oscar-nominated foreign film from last year, Paradise Now, Hood allows the camera to speak volumes by simply contrasting the expansive ghettos in the same frame as the city’s glittering skyline.

Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae in his first film) is a teenage street thug. Tsotsi isn’t even his real name. It’s slang vernacular for “thug.” His real name we won’t discover for the majority of the film. No one in Tsotsi knows his name either, even his own loose knit gang--dim-witted yes-man Aap (Kenneth Nkosi), Butcher (Zenzo Ngqobe), a psychopath who lives up to his name, and almost-school teacher Boston (Mothusi Magano)--who leave their Johannesburg slums (that have the feel of the Japanese shantytowns in Kurosawa’s Dodes'ka-den) each night in search of prey in the affluent city where they steal and kill without second thoughts.

Well, one of them has second thoughts. Boston confronts Tsotsi after the murder of man on the train, demanding to know if the young man has any decency in him. We don’t assume so. Our impression of Tsotsi is pure, unmitigated, ice-cold evil. That anything could change that impression is unthinkable. When Boston pushes Tsotsi too far, asking him if he’s ever loved or been loved in return, Tsotsi erupts, beating him to a bloody pulp.

Fleeing into the night, the nerves of his abusive and agonizing childhood unearthed, Tsotsi finds himself in front of the kind of home he’s never been inside--large, opulent and guarded by a wall. When a Mercedes pulls up in the driving rain and a woman gets out to open the security gate, Tsosti steals her car and shoots her when she resists.

It isn’t until he is miles down the road that Tsotsi realizes he is not alone. In the back seat, a small baby coos and cries. Why doesn’t he just kill it? Abandon it? Even leave it at a hospital or church? Apparently none of these thoughts occur to Tsotsi. He places the child in a large paper bag ironically emblazoned with the words “Expect More” and heads back to the shack he calls home.

Why he cannot abandon the boy is revealed in a series of flashbacks where young David, as Tsotsi was once known, watches his mother slowly dying of AIDS and his violent father drink himself into a monster. Suddenly, it becomes almost comprehensible how Tsotsi, abandoned as a child and left to fend for himself, could evolve into a kind of monster himself. Looking at the helpless baby in front of him, a lone spark of goodness jumps to life within the darkness of Tsotsi’s soul.

It does not roar into a flame all at once, of course. Chwenayagae’s performance brings great credibility to Tsotsi's transformation. It isn’t sudden and it isn’t complete. It's a gradual process and we see each step. (When a director can take a deplorable monster and, within the relative blink of an hour and a half, turn our reaction from disgust to sympathy, he’s a filmmaker to watch.)

Unable to feed the baby, Tsotsi enlists (at gunpoint) the help of a young widow with a small child, Miriam (Terry Pheto in her first film). At first Miriam obeys because she is afraid of Tsotsi and his gun. After all, a story she tells later makes it clear that Tsotsi or another hoodlum like him robbed her of her husband. But later, she breastfeeds the child because she cares for the baby and maybe even Tsotsi. There’s is not a romantic relationship. Their encounters are far too brief and too charged with danger for that. Instead, Mariam acts as a sort of angel to Tsotsi’s demonic rage. Perhaps he sees his own mother in her gentle touch and melodious song. By being kind and willing to care Tsotsi’s young charge, she is both a balm to the young man’s deepest pains and a roadmap from madness to sanity.

Ultimately, Tsotsi is convinced that he must return the child. But doing so will put him face to face with the angry husband and wife, now paralyzed from her injury and an antsy police force. In the final scene, Tsotsi, now, for the first time in the film wearing white, is surrounded on the street in front of the house by police officers, their weapons drawn on him as, weeping, he returns the child to his mother’s arms.

One journey has been completed but another is about to begin. If the first dealt with redemption, the second must address consequences. For the film Tsotsi, both journeys are inescapable. Tsotsi surrenders to his captivity, freer than he’s ever been before in his life.

To read the full review, click here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home