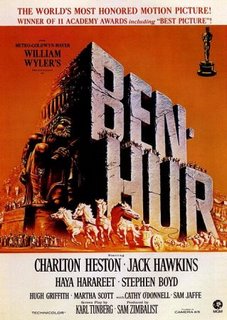

Ben-Hur

For the past year or so, I have been writing film and TV reviews at DVDFanatic.com. Here are synopsis' and links to those reviews.

I recently taught a college course on the “Epic Film” to a class of students, the oldest of whom was barely of legal drinking age. Unaware of a time in which computer graphics were not standard filmmaking props, the students reacted enthusiastically, yet cautiously, to a syllabus of films, the majority of which were as old or older than their parents.

As the semester progressed, their reservations turned into genuine awe. When Moses parted the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments, their heads nodded with satisfaction. When Cleopatra entered Rome in a magical procession, smiles pulled at the corners of their mouths. When David Lean’s camera lovingly caressed the swirling vistas of sand in Lawrence of Arabia, some emitted gasps. And when Judea Ben-Hur rounded the turns of the Jerusalem chariot stadium behind four glistening white stallions, they positively squealed.

After nearly 50 years, Ben-Hur still looks and acts every bit the part of the most Oscar nominated film in history.

When it was made in 1959, Ben-Hur was the most expensive film ever produced – and also one of the most lucrative. Smashing not only box-office records but Academy records as well (a staggering 11 Oscars—equaling but not surpassed by only two other films: Titanic and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King) including Best Actor, Best Director and Best Picture.

If there is one civilization that has dominated popular ideas of what a historical epic film ought to be, it is ancient Rome. Given how much of Western society is indebted to the Roman experience—our law, literature, language, architecture, administration and problems of empire—it is of little surprise that an empathy exists between our two cultures.

It is, perhaps, a paradox then, that Rome found itself alternating between the hero and the villain in so many epics of the Cold War era. Those films that dealt with Ancient Rome on a secular, pagan level had no difficultly elevating Roman society as a paradigm of civilization. However, when Rome was placed beside the tempestuous Jewish and early Christian elements of its history, Rome was always relegated to villainy, debauchery, and oppression. Ben-Hur, on one level or another, attempts to straddle both worlds.

Ben-Hur began its life as a novel, published in 1880 by Civil War general and devout Christian, Lew Wallace who wanted to write a book about the life of Christ without making Christ his central figure. Phenomenally successful, the book was adapted to the stage and not one, but two silent films (the second of these, the 1925 version, is included in this disc set) before becoming the blockbuster we know today.

When MGM decided to remake Ben-Hur, it was because their coffers were empty and competition with television was decimating their earnings and attendance. Cecil B DeMille’s remake of his own, The Ten Commandments was so successful that the studio hoped a Ben-Hur remake would rake in similar profits. Wagering everything they had, MGM spent over six years, built over 300 sets and hired over 50,000 extras to make their epic a reality.

The film’s protagonist is Judah Ben-Hur (played by Charlton Heston, the Epic’s darling), a wealthy Jewish Prince who undertakes both a harrowing physical and emotional journey through hatred, bitterness, compassion and ultimately forgiveness. Betrayed and sent into slavery by a Roman friend, he regains his freedom and returns for revenge, only to find a more powerful force at work in his life—redemption, birthed through a series of encounters with Jesus Christ.

Not simply a rousing adventure (and its fearsome sea battle and unsurpassed chariot race earn it that distinction), Ben-Hur is a film with a genuine heart at its core and, despite some instances of wooden acting, fully fleshed out personalities instead of mere cardboard cutouts. This classic epic is also an intimate epic, a film that never loses sight of its characters’ and their personal struggles in the midst of the large-scale pomp and production values. More than the sum of its grand parts, Ben-Hur is the story of a man and therein lies its eternal appeal.

To read the full review, click here.

I recently taught a college course on the “Epic Film” to a class of students, the oldest of whom was barely of legal drinking age. Unaware of a time in which computer graphics were not standard filmmaking props, the students reacted enthusiastically, yet cautiously, to a syllabus of films, the majority of which were as old or older than their parents.

As the semester progressed, their reservations turned into genuine awe. When Moses parted the Red Sea in The Ten Commandments, their heads nodded with satisfaction. When Cleopatra entered Rome in a magical procession, smiles pulled at the corners of their mouths. When David Lean’s camera lovingly caressed the swirling vistas of sand in Lawrence of Arabia, some emitted gasps. And when Judea Ben-Hur rounded the turns of the Jerusalem chariot stadium behind four glistening white stallions, they positively squealed.

After nearly 50 years, Ben-Hur still looks and acts every bit the part of the most Oscar nominated film in history.

When it was made in 1959, Ben-Hur was the most expensive film ever produced – and also one of the most lucrative. Smashing not only box-office records but Academy records as well (a staggering 11 Oscars—equaling but not surpassed by only two other films: Titanic and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King) including Best Actor, Best Director and Best Picture.

If there is one civilization that has dominated popular ideas of what a historical epic film ought to be, it is ancient Rome. Given how much of Western society is indebted to the Roman experience—our law, literature, language, architecture, administration and problems of empire—it is of little surprise that an empathy exists between our two cultures.

It is, perhaps, a paradox then, that Rome found itself alternating between the hero and the villain in so many epics of the Cold War era. Those films that dealt with Ancient Rome on a secular, pagan level had no difficultly elevating Roman society as a paradigm of civilization. However, when Rome was placed beside the tempestuous Jewish and early Christian elements of its history, Rome was always relegated to villainy, debauchery, and oppression. Ben-Hur, on one level or another, attempts to straddle both worlds.

Ben-Hur began its life as a novel, published in 1880 by Civil War general and devout Christian, Lew Wallace who wanted to write a book about the life of Christ without making Christ his central figure. Phenomenally successful, the book was adapted to the stage and not one, but two silent films (the second of these, the 1925 version, is included in this disc set) before becoming the blockbuster we know today.

When MGM decided to remake Ben-Hur, it was because their coffers were empty and competition with television was decimating their earnings and attendance. Cecil B DeMille’s remake of his own, The Ten Commandments was so successful that the studio hoped a Ben-Hur remake would rake in similar profits. Wagering everything they had, MGM spent over six years, built over 300 sets and hired over 50,000 extras to make their epic a reality.

The film’s protagonist is Judah Ben-Hur (played by Charlton Heston, the Epic’s darling), a wealthy Jewish Prince who undertakes both a harrowing physical and emotional journey through hatred, bitterness, compassion and ultimately forgiveness. Betrayed and sent into slavery by a Roman friend, he regains his freedom and returns for revenge, only to find a more powerful force at work in his life—redemption, birthed through a series of encounters with Jesus Christ.

Not simply a rousing adventure (and its fearsome sea battle and unsurpassed chariot race earn it that distinction), Ben-Hur is a film with a genuine heart at its core and, despite some instances of wooden acting, fully fleshed out personalities instead of mere cardboard cutouts. This classic epic is also an intimate epic, a film that never loses sight of its characters’ and their personal struggles in the midst of the large-scale pomp and production values. More than the sum of its grand parts, Ben-Hur is the story of a man and therein lies its eternal appeal.

To read the full review, click here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home