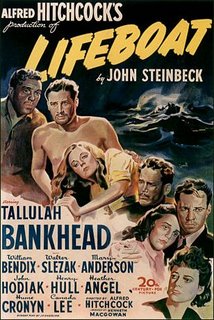

Lifeboat

For the past year or so, I have been writing film and TV reviews at DVDFanatic.com. Here are synopsis' and links to those reviews.

Lifeboat starts with a bang—literally. As the opening credits begin to roll, a ship slips beneath the waves, the victim of a Nazi U-boat, and the few survivors collapse into a tiny lifeboat, sailing toward an uncertain fate. The entire film takes place within the forced immediacy of the tiny craft, more like a stage play than a film. This has the effect of making the film tangibly claustrophobic. The tension developed within so small a space is palpable.

Foreseeing the Disaster Films of later years—Hitchcock puts a cross section of people from different backgrounds and beliefs together in a situation in which their lives are in danger and they must work together in order to survive. But at what cost, survival?

Lifeboat first appears as a generic war film—then appears as a standard piece of propaganda—then is realized as an allegorical dissection of the human spirit and fortitude in the midst of a claustrophobic hell, much of it by the characters’ own making.

The passengers, a microcosm of American and British society—flesh and blood representations of their countries (portrayed by believable but non-bankable stars)—include the worldly, high-society journalist who prizes possessions she no longer has, a ship worker whose torso is tattooed with ex-girlfriends’ initials, a good-natured but simple seaman who longs to dance with his girl despite an amputated leg, a nurse who finds she cannot heal her own wounds, a wealthy industrialist who realizes how pointless his pursuit of wealth has been, a radio operator turned lifeboat navigator, an ex-pickpocket who now seeks a better way of life and is ignored until needed, and, most interesting of all, a Nazi U-boat captain—easily the smartest, strongest and perhaps, the most likable person onboard.

It is the character of Willy, the Nazi, that made Lifeboat so controversial. Striking many as a blasphemous portrayal in such perilous times, Willy is not your stereotypical goon. He is given a non-threatening name and looks, he is a capable seaman where the others are completely incompetent, he is a skilled surgeon who performs the amputation, he is a multiple linguist, and he’s the only one who keeps his head when a storm threatens to destroy their lifeboat.

Not going completely against the feelings of the time, Willy has his dark side too. He manipulates the others, holds out information and water, and causes the death of one of the boat’s occupants. Should he be arrested? Should he be killed outright? Is he an enemy soldier, war criminal, or must the others in the lifeboat compromise to make use of his knowledge to save themselves?

The film is a moral education for the characters and they learn their lessons in awkward, messy, ugly steps. Already looking to the future and realizing that the Allies will win the war and must wrestle with the aftermath that is to come, Lifeboat subversively proclaims, “We have seen the enemy and the enemy is us.”

Are we so different than those we are fighting? With pervasive class, race and gender conflict throughout the Allied ranks, is Nazi Germany the only place where massive inequality and injustice festers? What happens when life’s props are stripped away and the real you is revealed beneath? What happens when all you thought important is shown to be irrelevant? What happens when the healer becomes a killer? Can mob mentality ever lead to justice? What links us together as human beings and what keeps us apart? In a life-and-death situation, do geographical lines on a map truly matter? Where is the line where our social identifications disintegrate and we are all simply human—and how quickly the masks snap back on?!

Lifeboat ends having raised far more questions than it answers. Much like war. After staring into the dark abyss, can we ever be the same again?

To read the full review, click here.

Lifeboat starts with a bang—literally. As the opening credits begin to roll, a ship slips beneath the waves, the victim of a Nazi U-boat, and the few survivors collapse into a tiny lifeboat, sailing toward an uncertain fate. The entire film takes place within the forced immediacy of the tiny craft, more like a stage play than a film. This has the effect of making the film tangibly claustrophobic. The tension developed within so small a space is palpable.

Foreseeing the Disaster Films of later years—Hitchcock puts a cross section of people from different backgrounds and beliefs together in a situation in which their lives are in danger and they must work together in order to survive. But at what cost, survival?

Lifeboat first appears as a generic war film—then appears as a standard piece of propaganda—then is realized as an allegorical dissection of the human spirit and fortitude in the midst of a claustrophobic hell, much of it by the characters’ own making.

The passengers, a microcosm of American and British society—flesh and blood representations of their countries (portrayed by believable but non-bankable stars)—include the worldly, high-society journalist who prizes possessions she no longer has, a ship worker whose torso is tattooed with ex-girlfriends’ initials, a good-natured but simple seaman who longs to dance with his girl despite an amputated leg, a nurse who finds she cannot heal her own wounds, a wealthy industrialist who realizes how pointless his pursuit of wealth has been, a radio operator turned lifeboat navigator, an ex-pickpocket who now seeks a better way of life and is ignored until needed, and, most interesting of all, a Nazi U-boat captain—easily the smartest, strongest and perhaps, the most likable person onboard.

It is the character of Willy, the Nazi, that made Lifeboat so controversial. Striking many as a blasphemous portrayal in such perilous times, Willy is not your stereotypical goon. He is given a non-threatening name and looks, he is a capable seaman where the others are completely incompetent, he is a skilled surgeon who performs the amputation, he is a multiple linguist, and he’s the only one who keeps his head when a storm threatens to destroy their lifeboat.

Not going completely against the feelings of the time, Willy has his dark side too. He manipulates the others, holds out information and water, and causes the death of one of the boat’s occupants. Should he be arrested? Should he be killed outright? Is he an enemy soldier, war criminal, or must the others in the lifeboat compromise to make use of his knowledge to save themselves?

The film is a moral education for the characters and they learn their lessons in awkward, messy, ugly steps. Already looking to the future and realizing that the Allies will win the war and must wrestle with the aftermath that is to come, Lifeboat subversively proclaims, “We have seen the enemy and the enemy is us.”

Are we so different than those we are fighting? With pervasive class, race and gender conflict throughout the Allied ranks, is Nazi Germany the only place where massive inequality and injustice festers? What happens when life’s props are stripped away and the real you is revealed beneath? What happens when all you thought important is shown to be irrelevant? What happens when the healer becomes a killer? Can mob mentality ever lead to justice? What links us together as human beings and what keeps us apart? In a life-and-death situation, do geographical lines on a map truly matter? Where is the line where our social identifications disintegrate and we are all simply human—and how quickly the masks snap back on?!

Lifeboat ends having raised far more questions than it answers. Much like war. After staring into the dark abyss, can we ever be the same again?

To read the full review, click here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home